How should we contend with a post-war Russia?

Neither with loving open arms or a punishing vengeance.

Conflicts are, by their nature, constantly evolving beasts that require our careful attention lest they devour us whole. The ongoing Russian-Ukrainian War should not have surprised those of us who have paid close attention to Russia and its relationship with the West over the past three decades. From the bombing of Belgrade in 1991 to interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, the Kremlin’s trust in the West in managing global security challenges has faded through time. Russia perceives the United States and its NATO allies as a threat to its existence and its “genuine sovereignty”; it has also viewed Washington as the source of “color revolutions” throughout the Newly Independent States (Post-Soviet States) of which Ukraine was also a “victim” of. Not only are we witnessing a type of war not seen in Europe since 1945, but we are also facing Russia’s lashing out of a long-suppressed desire to revolt against Western hegemony. The damage has been done. The unipolar moment is dead. Any attempt to restore it will be guided by destructive nostalgia, If we can accept this fact, then some pathway to a post-war resolution can be made. To set the foundations of a lasting peace, the West must be prepared to both contain and engage with Russia. The isolation, humiliation, or “cancellation” of Russia would only give rise to a state awash in resentment and ready to continue the fight.

We have to establish one clear parameter for our discussion: What will a post-Russo-Ukrainian War situation look like? In my view, the territorial status of the conflicting parties is irrelevant to the type of approach we should adopt for a peace settlement and our collective post-war attitudes towards the aggressor in question. Two approaches come to mind from our experiences in the 20th Century: Firstly, a punitive approach which will seek to either contain Russia, extract reparations, and dangle a reminder of persistent guilt not just over the Kremlin but over the Russian people too, just as the Allies did to the defeated Central Powers after the First World War; secondly, a reconciliatory approach which will aim to integrate once belligerent adversaries (though not shirking from the need to try war criminals), assist in reconstruction initiatives, and neuter jingoistic sentiments within all sides, just as the Western Allies did to the defeated Axis Powers after the Second World War.

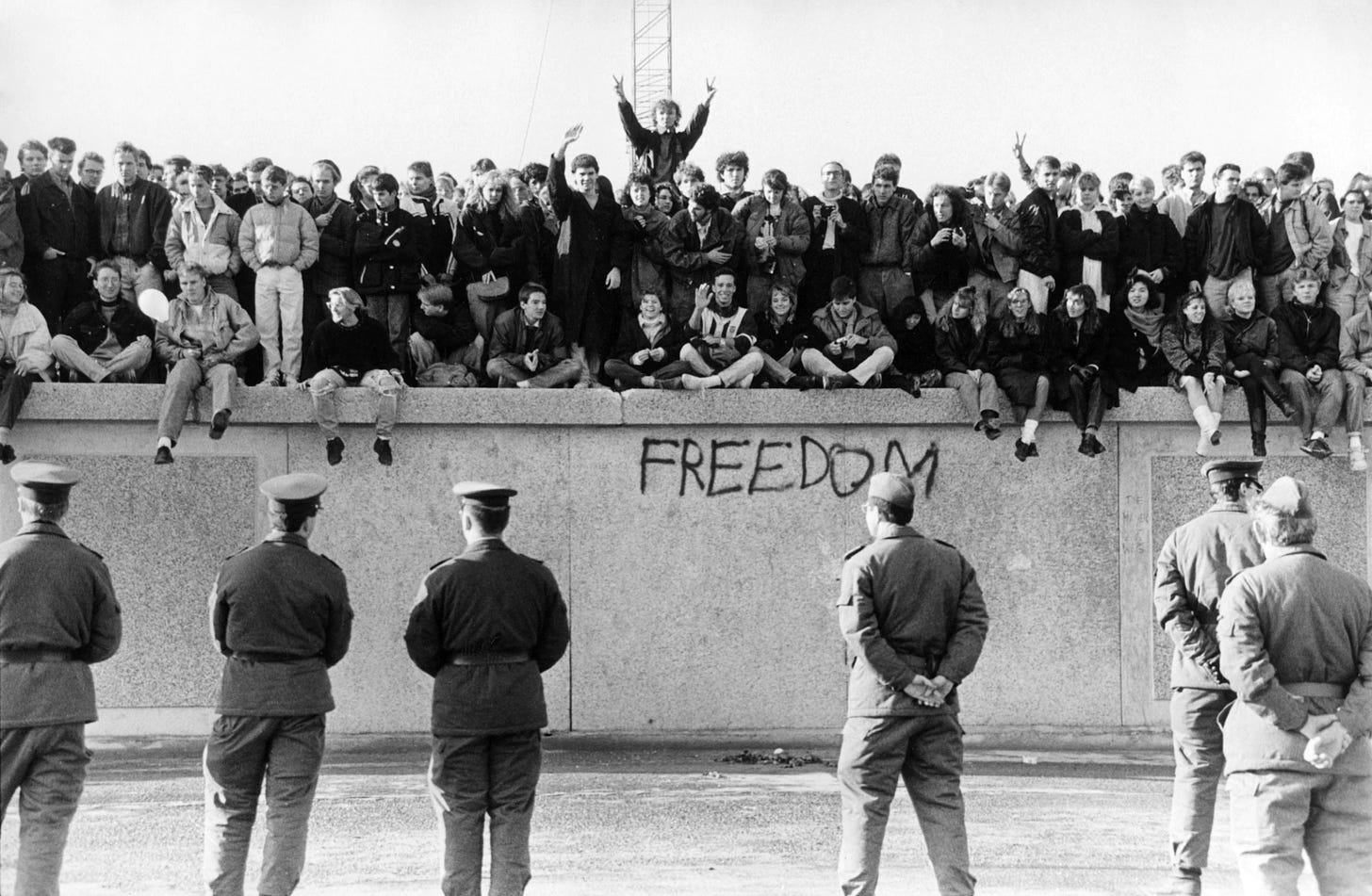

Certainly, the approach of reconciliation proved to maintain the “long peace” that we had only so recently bade farewell to. But this experience failed to inform the minds of those who “won” the Cold War with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the lowering of the Soviet flag over the Kremlin. Russia and the Newly Independent States (NIS) - excluding the Baltics - were, under the guidance of neo-liberal mantras, left on their own to develop free and unfettered capitalism which would, as the expectation was, turn them into prosperous democracies that would look “just like us”. This was a mistake. The 1990s in Russia and the NIS was a wild and painful time that was synonymous with gangsterism, the rise of oligarchs, and the weakening of state authority. It was precisely this smutnoe vremya (times of troubles) that gave rise to strong men like President Putin and his entourage from the security services to revive Russia as a great power - derzhava - like it was during its Imperial and Soviet days. For Russia’s decision-makers, it was necessary to demonstrate their strength and to show that the crossing of its “red lines” meant only regrettable consequences for the West.

There is no denying that Russia has violated international law on many counts. It violated the United Nations Charter, the 1975 Helsinki Accords, and the Budapest Memorandum to name a few. Reports of alleged war crimes against Ukraine desperately need to be investigated and any potential perpetrators identified to be tried in a legitimate court of law. Justice will have to be carefully and rightfully meted out to those who deserve it, but the belief that in a post-war situation that the entire Russian nation should be punished collectively is not just a faulty but dangerous idea. Just the same, a reconciliatory post-1945 approach might be too generous for aggressor states in the 21st century. A third approach of contained engagement, which synthesizes the two aforementioned approaches, might be most prudent for the future and our posterity.

“Speak softly,” said President Theodore Roosevelt, “and carry a big stick; you will go far.” Contained engagement, I argue, continues the legacy of Roosevelt’s realpolitik while retaining the ethos of Washington’s Cold War diplomacy. Autocrats need to be contended with, especially when they have pernicious plans that extend beyond their borders; but, it must be done with a certain finesse that obstructs their plans without strengthening their authority at home. According to a recent Levada Center poll, 74 percent of Russian respondents believed that the goal of Western sanctions was to “humiliate” Russia; Putin’s approval rating rose from 65 percent to 83 percent after the initiation of the invasion. Already, the use of a big stick fails to bring about the desired effect; doing the same after an end of hostilities would only instill resentment and give reason for Russia to lash out once more.

Safeguards to build peace must be agreed upon mutually, a major factor that led us to where we are now was precisely the failure of the West to jointly engage with Russia when its early red lines were drawn. Washington and Moscow will continue to persist as the seats of power for much longer; even though the unipolar moment has elapsed, American power remains unmatchable by a single state, and Russia will endure as it has for hundreds of years. Where the two capitals can find common ground, on matters like climate change or necessary arms control, cooperation must continue.

At our current moment, Ukraine's struggle for its freedom continues, but the West must ensure that it does not spiral beyond its control. It must begin to think about what it must do when it ends. Currently, the West demonstrates its inability to act with foresight, restricting Russians from studying in Western academic institutions, banning them from taking the TOEFL English exam, or canceling classical Russian writers from Dostoevsky to Pushkin will not aid the West’s cause. Rather than making the people turn against the regime, it will inadvertently strengthen it by giving the impression of Western “Russophobia”. As one Russian opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza wrote, behind prison walls, for the Washington Post, “Instead of generalizing and painting all Russians as enemies, as some shortsighted Westerners seem to be doing, it is important to find ways to start a dialogue with that part of Russian society that wants a different future for our country”.

The West must live up to its ethos and remain open to those who want to be free. Supporting a war-averse Russian emigre population who can inspire their compatriots at home will be a more potent driver for change. The ratification of the 1975 Helsinki Accords, an important victory of the detente period, also meant that the Soviet Union and its satellites pledged to uphold human rights. A byproduct of this remarkable event was the formation of “Helsinki groups” throughout the Eastern Bloc which monitored the implementation of the principles enshrined in the accords. Even though they were actively suppressed, it allowed human rights oriented civil society to take root. This was achieved not by walling out those behind the Iron Curtain. Even though President Ronald Reagan called on Gorbachev to “tear down” the Berlin Wall, it fell because it failed to serve its purpose of keeping East Germans in. Hungary and Czechoslovakia, after ending their communist dictatorships, opened their borders allowing East Germans to enter the West via Austria. In countries where the people’s votes matter little, they vote with their feet. We cannot build new walls that will keep those who we want to be “more like us” out. Speak loudly and carry a big stick; and we will go nowhere.